Research

Our research aims to understand how to design and build distributed systems worthy of the trust that government, businesses, and the public increasingly put in them. We investigate both foundational and applied aspects of reliable distributed computing; at its best, our work leverages the former to shape the latter.

Between 2014 and 2018, much of of our group’s attention has focused mitigating the tension between consistency and performance.

Modular Concurrency Control The last decade has seen a rift between the proponents of the ACID paradigm, which offers programmers an elegant and powerful abstraction for structuring applications and reasoning about concurrency, and the advocates of BASE, an alternative approach based on more limited isolation guarantees and a more streamlined API. One of the main goals of our work has been restore the promise of ease of programming combined with availability and performance that has become a casualty of the ACID vs BASE debate.

Our starting observation is that, just as Pareto’s principle predicts, transactions are not equally demanding: for many applications, it is only a few critical transactions that test the performance limits of ACID. We leveraged this observation to develop the theoretical foundations (in particular, the new abstraction of BASE transactions and the notions of isolation necessary to support it) that enable the ACID and BASE paradigms to coexist in the Salt database. We show that by just rewriting those few performance critical transactions as BASE transactions (leaving all other ACID transactions unchanged) Salt can boost throughput (e.g., for TPC-C) by close to an order of magnitude. More details about Salt can be found here.

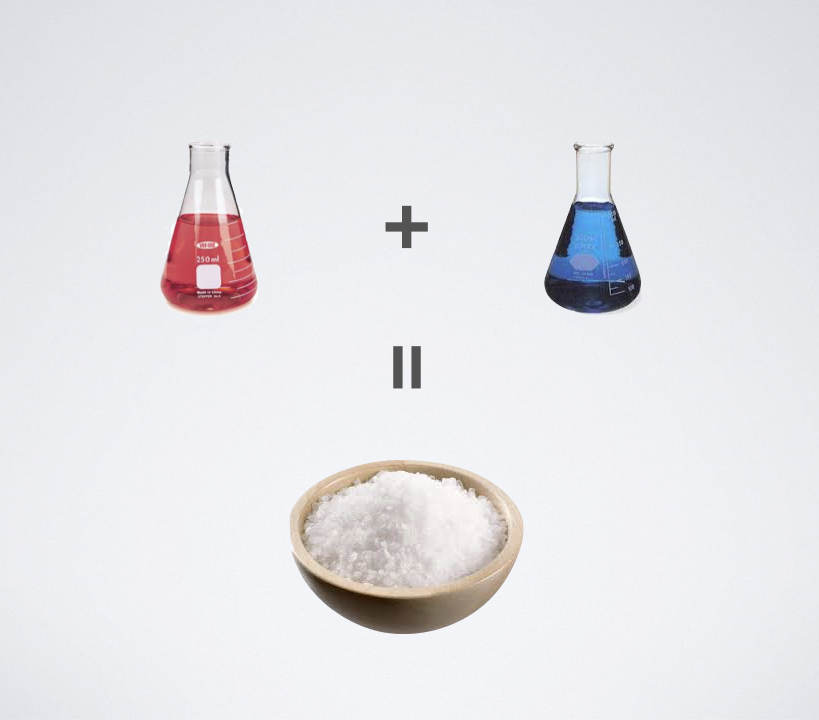

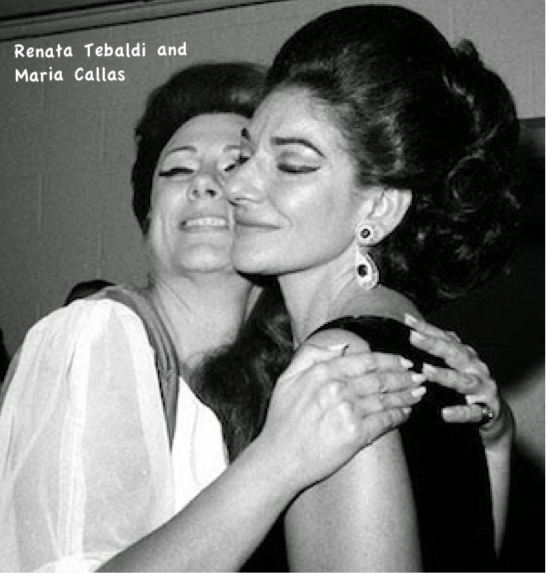

Our next step aims for a more ambitious objective: bringing the performance of ACID applications within striking distance of a BASE-reimplementation without requiring any programming effort from the developer. The secret sauce is Modular Concurrency Control (MCC), a new approach to federating concurrency controls mechanisms. MCC partitions transactions in groups, and gives each group the flexibility to choose the concurrency control mechanism that can more efficiently regulate conflicts between its transactions. Charged with regulating concurrency only for the transactions within their own groups, these mechanisms can be very aggressive and yield more concurrency while still upholding safety. CC mechanisms are mapped to the nodes of a tree, and each parent CC mechanism is reponsible for regulating conflicts across the groups of transactions managed by its children CCs More details about two databases that leverage MCC, Callas and Tebaldi, (what Lorenzo thinks about when you mention “The Sopranos”) can be found, respectively here and here. We are currently working on fully automating in Tebaldi the configuration of these hierarchical federations of CC mechanisms.